The Case for Armed Resistance: Where ‘Peaceful Coexistence’ Was Not Enough

Exploring the armed struggles of the ANC in South Africa and FLN in Algeria during their settler-colonial occupations, this post explores the justifications for and merits of armed resistance, while touching on the work of Fanon.

Throughout history, armed resistance has been viewed with scepticism. So-called ‘peaceful’ solutions, which are often an excuse for inaction, have been preferred by onlookers. But these calls are often overshadowed by one glaring issue, which is that the coloniser and the colonised do not share the same notion of peace.

The misplaced pacifism in today’s discourse has dampened the validity of armed struggles against the occupiers of today, like that of Palestinians’ against the Zionist regime. Even those who voice support for Palestine semantically evade the question of an armed struggle as if the use of it would affect the palatability of their resistance.

As exemplified most recently by the worldwide reception of civilian-led resistance in Ukraine, with weapons and homemade Molotovs in hand, the dislike for armed resistance has never been a question of morality - it is rather one based on selectivity; on who is and isn’t allowed to engage in these acts based on their appearance and what they symbolise. What can be understood even by this selective support is that we all possess an innate moral understanding that the weight of oppression can be justifiably relieved by any means necessary including force - so long as the people being oppressed are deemed worthy of doing so.

What is made abundantly clear about those who adopt this selective approach is that they are not concerned with liberation; they are concerned with its readability and how morally acceptable it appears, despite the parameters of what is wildly changing depending on whose armed resistance is under discussion.

Far from being an inadequate solution, the historic record of successful armed liberation movements has proven that it can be more than just a viable option; it can be a necessity to dismantle colonialism, to combat what is in essence a form of violence itself. In this post, we touch on the work of Frantz Fanon while exploring some of the examples of armed resistance in settler colonial contexts to understand its applicability, and how it is a morally justifiable solution to dismantle colonialism even today. Though there are countless examples of this stretching from Cuba to Vietnam, for the sake of time we focus on unpacking the armed struggles of the ANC in South Africa and the FLN in Algeria.

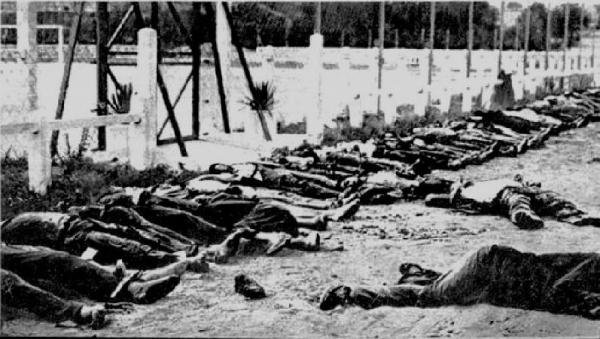

Exploring the Alternative: colonial responses to non-violence

It’s often the response to non-violent resistance which paves the way toward an armed struggle. This was the case for Algeria in 1945, after the Sétif and Guelma Massacres. The French had broken out into celebrations during the victory of the allied forces at the end of World War 2, at the same time that thousands of Algerians were growing in anti-colonial sentiment after years of brutal treatment. Many Algerians took to the streets, peacefully protesting for civil rights, and the right to independence which was promised to them by the French on the condition that they aided the French during the war through service. As the number of Algerian protesters increased, so did French anxieties. French troops were ordered to attack with disproportionate force; they began firing into the crowds, killing unarmed civilians. Fighting between the two groups intensified as the French pillaged through villages in ground offensives, and carried out aerial bombings, massacring thousands. Though numbers range, it is estimated that over the span of a few weeks, up to 45,000 Algerians had been killed.

In many ways, these massacres formed the basis of the armed struggle in Algeria, as it amplified the hypocrisies of the ‘civilising mission’ of French colonial rule, as well as their disregard for Algerian life. It became a catalyst for the War of Independence and formed the revolutionary spirit of those who would later lead them in their fight, such as Ahmed Ben Bella who would later become the face of the FLN’s armed struggle. He came to the realisation through this event that the French had no interest in compensation or compromise, and would have to be fought with force.

***

Before turning to arms, the ANC had adopted a more muted approach to the struggle against apartheid. The organisation was initially created in 1912 and was committed to restoring the right to vote for black and mixed-race South Africans through nonviolent, peaceful protest. So what was it that caused the turn to armed resistance?

One event was the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960. As part of the Defiance campaign, members of the ANC and other groups began protesting through non-violent acts of civil disobedience. One such method was Pass-burning. Passes were an internal passport system enforced by law to facilitate segregation. Black South Africans were made to carry passes at all times which among other things, limited their movement and their ability to travel and work, essentially treating them as second-class citizens. The police responded to the non-violent protest by opening fire on the crowd, savagely killing around 69 people while leaving many others injured.

This act was done under a backdrop of tightening colonial control which severely affected the black population's quality of life. Black South Africans were unable to own or rent real estate outside of areas designated to them, and shanty towns on the outskirts of major cities were growing as black South Africans were prevented from living in the cities. Black labourers were banned from managerial positions as well as trade unions, creating no prospect for career progression or job security. Surveillance, killings and imprisonment of activists continued. With thousands of activists behind bars and conditions worsening, people began to feel apathy towards the ANC, as their efforts were not creating any substantial change to the apartheid, Manichaic system. Even the sole goal it had set out to do in 1912, to reinstate the black voting rights, had not yet been realised.

While some believe that talks of armed resistance began long before Sharpeville, others see it as the main turning point. Soon after the massacre, 2,000 activists were imprisoned and the ANC and PAC were outlawed, forcing many members to go underground.

Here, the colonial system showed clearly, as it has always done, that it did not care for the concerns of its subjects, even when they were wrapped in peaceful packaging. Non-violent resistance is usually proposed under the assumption that the perpetrator is reasonable; that it has the capacity to yield to the needs of the ones it suffocates, and that it wants to exercise this ability. However, as Fanon suggests, a colonial system cannot be treated as if it has reasonable, humane, and logical faculties:

“Colonialism is not a thinking machine, nor a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.”

- Frantz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, [2]

It was under these brimming conditions that, true to Fanon’s words, the then President of the ANC’s Youth League Nelson Mandela along with his colleagues came forward voicing a desire to pivot from non-violent protest to armed resistance. He voiced the feelings of those who were increasing in apathy towards non-violent resistance:

Snippet of Mandela’s first TV Interview with ITN, 1961 // Link to interview

Within Mandela’s conclusion, we see a nod towards something mentioned by Fanon who suggests that within the Manichaic life that colonial systems produce, it is the natives' realisation of his own humanity that allows armed resistance to become a more palatable option:

“At times this Manicheism goes to its logical conclusion and dehumanises the native, or to speak plainly, it turns him into an animal…The native knows all this, and laughs to himself every time he spots an allusion to the animal world in the other’s words. For he knows that he is not an animal; and it is precisely at the moment he realises his humanity that he begins to sharpen the weapons with which he will secure victory.”

- Frantz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth [1]

This marked a change in the understanding of effective resistance. It was the realisation that non-violence in response to systemic, violent oppression, would simply not work to dismantle violent apartheid practices that were so deeply interwoven into the state system. This weaving went beyond the psyche of the State and into its institutions, emboldening them to see its subjects not as humans, but as things that could be controlled, herded and killed if they rebelled. It was the realisation that an oppressor, whose existence is fuelled by violence, will not see or appreciate the humanity behind non-violent resistance.

Learning from the aggressor: making life unbearable for the coloniser

In Algeria, continued colonial suffocation led to the formation of the National Liberation Front (FLN) which would lead the fight against the French in the brutal War of Independence in 1954. The period of non-violence had largely come to an end as the FLN had propelled itself into an all-out armed struggle, in pursuit of a sovereign Algerian state. The FLN carried out strategic bombings and became sophisticated in their use of guerrilla warfare against the French, which would later become an inspiration for others revolutionaries like Che Guevara. Fighting was brought to the cities which increased international and domestic pressure on the regime, and a general strike was issued, which caused great economic damage to the regime.

Strikers marching the streets of Algiers, 1957

Echoing the years prior, the French responded with brute force. They used tactics like napalm, torture, forced labour in concentration camps, and mass rape. Psychological warfare also became a key tactic for the French by targeting FLN family members and causing false flag events where turned FLN members would cause havoc to frame the FLN, in order to spark distrust and fear among the public.

Similarly in South Africa 1961, shortly after the Sharpeville massacre, the ANC’s armed struggle began under the armed wing of the organisation called MK, and was mainly coordinated by Mandela himself from underground cells. The attacks escalated quickly over the years from sporadic blows to a systematic, sophisticated attack which overwhelmed the colonial system. The MK went from coordinating 11 attacks mainly on railway lines in the year of 1977, to a serious escalation in the 80s where at least one attack was carried out a week on police stations and strategic installations. The years in between were no different - methods of armed resistance continued, including car bombings, shootings and sabotage, while new members were trained in guerilla warfare with the help of the FLN of Algeria, and the rebels of the ongoing decolonial struggles in Cape Verde, Angola, and Mozambique. These attacks shook the regime, striking fear in the settlers all the way up to government officials who could no longer suppress the resistance as easily as before.

As Fanon suggests, violence can only be quelled with greater violence. It is a tactic that is learned from the colonisers themselves, who show that there is no other way to bargain than through threat. The notion of peaceful conflict resolution where both parties are left content, as is often proposed by onlookers requires two things; that the colonial power is interested in compromise, and that the colonised are willing to sacrifice some of their basic freedoms in order to respect that. Believing the former would negate everything we have come to know about exploitative colonial rule that is only made to aid the interest of the colonial state, while the latter is simply unfair when basic rights are in question. The only thing that the colonial power will bend to is a sizeable threat - one that has the potential to get in the way of their interests. In order to form a sizeable threat, one can and should work in the same language of the coloniser, and that is violence.

Armed Resistance and its bargaining power

This new kind of resistance in South Africa had given activists a form of leverage that had not been enjoyed before. Rather than stifle the resistance after Mandela’s imprisonment in 1967, it gave the resistance bargaining power. Foreign investors became increasingly reluctant to pour their wealth into the country as political instability continued, and foreign leaders like Margaret Thatcher were forced to tell the regime to enter into negotiations with the MK and release Mandela under domestic pressure. This international pressure, coupled with the increasing domestic chaos caused by the MK pressured the South African government to enter into talks with the MK. Under the leadership of Botha, Mandela was offered release on the condition that he denounced violence as a political weapon and ordered the MK to halt the resistance. Mandela refused:

“What freedom am I being offered while the organisation of the people remains banned? Only free men can negotiate. A prisoner cannot enter into contracts.”

- Nelson Mandela

The violence escalated, and under the leadership of De Klerk who was keen to protect South Africa’s international reputation, Mandela was again offered release in 1989, only if he was to denounce communism and again reject the use of violence as a political weapon. Mandela again refused, stressing the importance of armed resistance as a bargaining tool. As violence once again increased and international pressure boiled over, the government was left with no choice but to succumb to the conditions of the resistance. On the 11th of February 1990, Mandela was released from prison, and ANC was legalised.

Nelson Mandela & his wife Winnie Mandela, shortly after his release from prison on 11th February, 1990

Through this, we see how armed resistance can give leverage to the anti-colonial struggle. Mandela was able to bargain largely because of the threat of violence which became too much to bear for the colonial regime, and forced them to bend to the needs of the resistance. It packaged the struggle in a language that the coloniser would understand and was all too familiar with which was the threat of force, and what ultimately led to the success of the resistance.

***

Conclusion

Armed resistance occurs alongside the realisation of the humanity of the native, by the native, while living under the Manichaic system that colonial regimes impose on them. It is an awareness of the fact that they cannot be herded like animals, massacred, or deprived of basic rights, and that when that does happen, they have every right to fight back. As suggested by Fanon, this is often forgotten by the native, whose memory of his humanity fractures after the decades, even centuries-long attacks by the colonialists which take both psychological and physical forms, and seek to dehumanise and break him down completely. But often times this memory is pieced back together with the help of the colonialists themselves, whose aggressive and violent response to non-violence & peaceful protests angers the oppressed enough to remind them of their humanity, while unveiling the reality that colonial states are not here to compromise and never will with a category of people they seek the exploit. In this way, non-violence is often deeply embedded into the story of armed resistance, as it is often the response of the coloniser to it which convinces the colonised that this method cannot work on its own, as was the case in both South Africa and Algeria.

However, the onlookers of colonial struggles often lose sight of the natives' humanity more so than the natives themselves. They are the ones who become desensitised to the violence of the oppressor, to the dynamic of the coloniser/colonised relationship after years of repeated media exposure, and often force the oppressed to function within the binary of non-violence if they wish for their struggle to have international acceptance and recognition. Looking into the experience of the FLN and ANC sheds light on the settler colonial methods of oppression which are all too familiar today, and how non-violence is not always enough to combat them. It is one of the only methods that the coloniser has shown the capacity to understand, because it is the only one it deals in. This is where we understand the limits to non-violence, and how for an oppressed group who are deprived of basic rights and live under conditions of constant brutality, armed resistance can become the only viable option for freedom.

Sources Used:

[1] Frantz Fanon, Concerning Violence, Wretched of the Earth, p.42-43

[2] Frantz Fanon, Concerning Violence, Wretched of the Earth, p.61

Musa Al Sadr: a Brief Exploration into the Clerics Political Legacy

As part of the political profiles series, this article offers a brief exploration into Musa al Sadr’s contributions to the Shi’i political Awakening of Lebanon.

“Whenever the poor involve themselves in a social revolution, it is a confirmation that injustice is not predestined.”

Image link: Musa al Sadr

The cleric's contribution to Shi’i Lebanese political thought and resistance is hard to miss. Through his charismatic leadership, an entire community was led out of political quietism into active resistance against a negligent government, planting the seeds to what would be Lebanon’s Shi’i political awakening for decades to come.

Sadr, born in the Iranian holy city of Qom to a Lebanese Ayatollah, arrived in Lebanon in 1959. With familial roots in Iran, Iraq and Lebanon, his background automatically tied him to a transnational tradition which ideologically bound the Shia of these areas together, contributing to his respected status across the international Shi’i community, as well as those of Lebanon.

At the time of his political ascendancy in the early 60s, Southern Lebanon was home to the impoverished and destitute Shia minority, which had been a product of years of government neglect that had pushed them to the very bottom of all socioeconomic indicators. Shi’i politics was monopolised by elites and their extensive patronage networks, which excluded average members of society. Though frustration over their neglect began to boil over, the Shias lacked the political organisation and motivation required to challenge these issues.

It was within this context that Sadr found his political calling. The next sections will unpack some of his main contributions to the Shi’i political awakening of the South, and what political legacy this has inspired.

Shi’i political activism

Perhaps one of his most important contributions to political thought was his firm belief in social revolution; to him, change could only be possible if it was a bottom-up, people led movement - one that required political and social organisation, as well as broad based communal support. Political activism was the means through which the impoverished could finally be pulled out of their destitution, giving them the platform to demand change.

Thus, appalled by the socioeconomic conditions of the Southern Shias and their severe underdevelopment, he began his campaign of reform through his role as Chairman of the Lebanese Islamic Shi’i Council, marking the first representative body that gave Shias exclusive representation, independent of Sunni Muslims. Through it, he called for the construction of schools and hospitals as well as wider political reform, which would finally end the period of isolation that cut them off from Lebanese society, and integrate them within its institutions. One of his biggest long term accomplishments was in education, through the establishment of the vocational institute in the Southern town of Burj al-Shimali [1], which has now become an important symbolic landmark of his legacy. He also demanded better military and defence measures that would protect the South from becoming the target of Israeli attacks.

These measures politically mobilised the Shia and improved their aspirations by giving them a new hope that their fortunes could change. He founded new groups concerned with protecting them, such as Harakat al Mahrumin (The Movement of the Dispossessed) in 1974 as well as its military wing Amal (Hope), while ideologically inspired other groups such as Hezbollah. In this way, his teachings have informed the ideological orientation of a generation of political leaders, many of which continue to shape Lebanese politics today. Hassan Nasrallah, the current leader of Hezbollah was one of these men, who at the young age of 16 [2] gained early political experience as a fighter for the Amal movement.

Unity

Sadr proved himself to be a pragmatic leader; though he was primarily concerned with uniting and organising the Shia, he extended his calls for unity beyond sectarian lines to the many different factions of Lebanese society. Harakat al Mahrumin itself, along with Sadr, was founded by Gregiore Hadad, the Greek Catholic Bishop of Beirut. It aimed to be a voice for the oppressed, but was significant in that it did not limit itself to any particular ideology; it aimed to represent all impoverished communities who had experienced government neglect regardless of their ideological orientation. He also gave regular speeches which attracted thousands, in which he invited people to look beyond social divisions and unite to end injustice. It was this pragmatism that allowed Sadr to expand his support base beyond sectarian lines despite his own firm belief in Shia Islam. His approach proved useful in overcoming Lebanon's societal divisions, ensuring the necessary inter-communal support needed to ignite any significant level of change. This approach later informed Hezbollah’s ideology, which has made a point of advertising its support for and protection of Lebanese Christian communities.

A symbolic legacy; ‘the man of double identity’

The controversy surrounding Sadr’s disappearance after attending a conference in Libya in 1978 has bound him to the concept of martyrdom, adding another symbolic layer to his legacy. It was another loss which had struck the hearts of Shias, as his story was now tied to the all-too familiar experience of prominent Shia figures and adherents throughout history; one that typically ended in oppression, sacrifice, and an untimely death. Ayatollah Khomeini, the father of the Iranian Revolution, did not hesitate to make him a representation of sacrifice for a greater cause, to inspire the next generation of Shia militiamen and political thinkers to keep on the path of revolution. Sadr was no longer just a Lebanese reformer, but part of a broader Shi’i tradition that went beyond state boundaries;

“Musa al Sadr himself came to serve an entirely new function. He was a man of double identity, claimed by the Iranians and by the Shia in Lebanon; he embodied the bonds, both real and imagined, between the two.”

- Fouad Ajami in The Vanished Imam: Musa Al Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon. [3]

***

Musa al Sadr's contribution to the Shi’i political awakening of the late 60s and early 70s is incomparable. One man's plight changed the fate of millions of Lebanese Shias who had become nothing but an afterthought before his ascendancy. As a man of great intellect and pragmatism, he was able to toe the line between Islamic-inspired reform and inter-communal unity; between political activism and Islamic spiritual guidance. Through this, he brought a new framework with which to approach issues of the disadvantaged; one that has inspired a generation of political reformers and religious thinkers today.

Sources Used:

[1] Augustus R. Norton, Hezbollah: A Short History (3rd Edition)

[2] Le Monde Patrice Claude, Mystery man behind the party of God

[3] Fouad Ajami, The Vanished Imam: Musa Al Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon

[4] Anoushiravan Ehteshami & Raymond A. Hinnebusch, Syria and Iran: Middle Powers in a Penetrated Regional System